Autobiographies are to some extent egocentric, written by people who are narcissistic enough to believe the world really cares how they lived and what they did. Important public figures have a right to feel that way, but many have the humility it takes to let others write their biographies.

Autobiographies are to some extent egocentric, written by people who are narcissistic enough to believe the world really cares how they lived and what they did. Important public figures have a right to feel that way, but many have the humility it takes to let others write their biographies.

Maggie O’Farrell is not an important public figure yet has chosen to write an autobiography comprised of 17 stories of near-fatal experiences that she thinks somehow make her story interesting. Some of them are interesting but many, as she herself admits on page 209, point out that, “It’s me who is the idiot.”

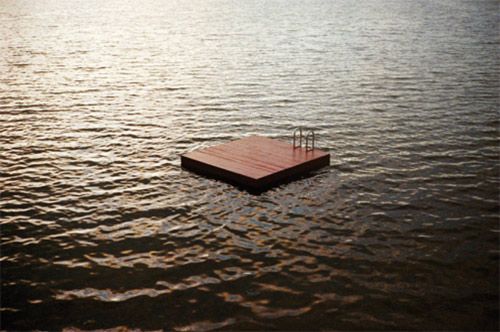

She makes that judgement after she recounts carrying her infant son on her back while swimming to a platform far from shore and almost failing to get there. “He can’t swim,” is what she says kept occurring to her far too late to do anything to correct the situation. Neither could she swim, at least not very well, which is something she knew going into the situation.

That incident is emblematic of many in the book in which she fails to factor in her childhood experience with encephalitis that left her somewhat physically and mentally disabled. As a teenager, for example, she jumped off a pier into deep water and was unable to orient herself properly to swim upward and free herself of the water. She admits at the end of that tale that she knew what might happen before she jumped.

That incident is emblematic of many in the book in which she fails to factor in her childhood experience with encephalitis that left her somewhat physically and mentally disabled. As a teenager, for example, she jumped off a pier into deep water and was unable to orient herself properly to swim upward and free herself of the water. She admits at the end of that tale that she knew what might happen before she jumped.

There are other tales that do not depend on her disability for an explanation of why she put herself in harm’s way. Simple adolescence is a fine explanation for a couple of them, and ignorance of a foreign country’s geography explains another.

The incident that flummoxed me was her decision to get pregnant knowing full well that a complete natural birthing experience might be impossible and that a caesarean section would be necessary. She then blames the doctor for her troubles in the birthing room because he refused to plan ahead for the surgery. Yes, he was guilty of a sort of misogynistic malpractice, but it was irresponsible of her to become pregnant in the first place, or at least to become pregnant without finding a doctor who would help her develop a fully formed birth plan.

Where Ms. O’Farrell cannot blame her condition, she likes to blame others for her difficulties. When she walks alone on a rem ote mountain path, she notes but ignores the presence on the path of a man who appears to be dangerous, but then later blames him for approaching her in a dangerous way. She then does a poor job of explaining the incident to the police, but accepts no responsibility for his fatal attack on another woman.

ote mountain path, she notes but ignores the presence on the path of a man who appears to be dangerous, but then later blames him for approaching her in a dangerous way. She then does a poor job of explaining the incident to the police, but accepts no responsibility for his fatal attack on another woman.

I think of Ms. O’Farrell as narcissistic enough to see herself as a blameless wanderer through a life we all live, full of mistakes and misjudgments, and circumstances we cannot control that endanger us. Is I am, I am, I am a worthy book? I think not, and I do not even include in that judgment my objections to Ms. O’Farrell’s overly wordy, over-polysyllabic writing style!

Recent Comments