I had a terrible time motivating myself to write this report. Like Hampton Sides’ other works, In the Kingdom of Ice is a clear and compelling narrative of a daring adventure, but this one ends on a tragic, sad note. Perhaps this is pure 21st Century hindsight, but it seemed to me that the venture was an unnecessary waste of men’s lives and money.

I had a terrible time motivating myself to write this report. Like Hampton Sides’ other works, In the Kingdom of Ice is a clear and compelling narrative of a daring adventure, but this one ends on a tragic, sad note. Perhaps this is pure 21st Century hindsight, but it seemed to me that the venture was an unnecessary waste of men’s lives and money.

That is because that Lt. George Washington De Long was as brave and capable a seaman as you could find, one who led his men with superb managerial and motivational skills on a mission to reach the North Pole, but had the sad result of leading most of them to their doom in the snowy wastelands of sub-zero Northern Siberia.

The foundation of polar exploration at the time of this adventure (De Long set sail on the Jeanette in 1879) was the belief widely held by the leading cartographers and geographers of the day, led by August Peterman, that north of the ice pack that locks in Greenland and much of North America would be found a warmer sea surrounding the North Pole. The theory of navigating to that sea was that warm waters of either the Gulf Steam or the Kuro Siwo Current (now called the Japan Current) would enable a stout ship to cut a channel through the ice pack from the North Pacific or North Atlantic into the Polar Sea.

De Long had participated in a rescue effort of an earlier failed effort that had been attempted going north on the west side of Greenland, and the experience inspired him to explore the polar region, and so he took on the venture to find the North Pole. Contemporary thinking had it that the ice pack flowed clockwise making it more likely that a path north through the Bering Strait and the Bering Sea would be successful in getting to the pole.

Financed by New York Herald Publisher and raconteur William Bennett, the newly married De Long acquired a ship, had it renamed Jeanette for Bennett’s sister and commissioned as a US Naval ship. It was fitted for the rough duty of polar exploration by Navy engineers at Mare Island who in fact thought the ships capabilities for navigating through the ice pack to be almost laughable.

De Long retained a very competent crew of 31, and set out from San Francisco, stopping in Alaska to pick up sled dogs, sledges for them to tow and big stocks of food, coal, and other supplies. He didn’t know it but passing his ship coming south through the Bering Strait was a US Coast and Geodetic Survey ship that had just finished an extensive multi-year survey of the Bering Sea and had determined conclusively that there was no possibility that the Japan Current was warm or strong enough to be of any use in cutting a channel to the Polar Sea.

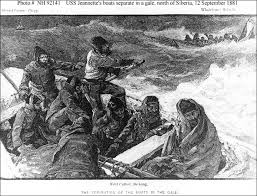

As now seems inevitable, the Jeanette became locked in the ice north of Siberia, ultimately crushed and sunk, leaving all 31 men stranded some 700 miles north of the Asian continent. They took three boats, that number of sledges to carry them on, as much food and other supplies as could be loaded into the boats, and started marching south across the ice. The theory of clockwise rotation of the ice pack was proven correct as the southbound trek of the men ended up taking them north until De Long realized the problem. By this time, he had also realized that the warmer Polar Sea was nothing but wishful thinking.

Upon finding open water, the three boats were trying to stay in line, but a gale blew them asunder and most of the remaining narrative is from DeLong’s “Ice Journal” that he kept after the Jeanette sunk. De Long and the men with him men ultimately got to the Lena River Delta, a very messy series of river fingers flowing onto a shallow swath of the Laptev Sea, so shallow that the boat was ultimately abandoned. It should be said that these men spent much of their time wet as well as icy cold in weather that commonly went as low as -400F.

Upon finding open water, the three boats were trying to stay in line, but a gale blew them asunder and most of the remaining narrative is from DeLong’s “Ice Journal” that he kept after the Jeanette sunk. De Long and the men with him men ultimately got to the Lena River Delta, a very messy series of river fingers flowing onto a shallow swath of the Laptev Sea, so shallow that the boat was ultimately abandoned. It should be said that these men spent much of their time wet as well as icy cold in weather that commonly went as low as -400F.

When they finally landed on what passed for dry land, the crew found themselves in a constant battle with gale force winds and snow. They were able to make camp now and again in shacks constructed for hunting parties, and they also found some food by shooting game and fowl.

Ultimately De Long had two men break off to try finding some sort of civilization. The crew from one of the other boats had found a settlement south and east of the Lena and the two men and that crew ultimately joined up. The crew of the third boat was never found.

Three of the survivors, assisted by some natives and Cossacks put a party together in the spring to hunt for and rescue De Long, but while they found the men, they were buried in the snow, dead from starvation and frostbite – they had even eaten their leather boots and parts of their garments.

The Russian Tsarist government helped the survivors recover and get back to New York carrying as much in the way of artifacts as they could. Fortunately, they recovered the ship’s log and De Long’s Ice Journal which were later edited and made into books by his widow.

This made for a tragic ending to a heroic story laced with great leadership wasted on a mission with an objective so flawed that it was doomed to fail before it started.

A great read about a wonderful adventure with a very sad end to it.

Recent Comments