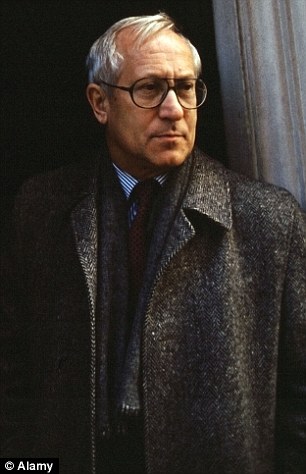

Oleg Gordievsky . . . lemme think . . . hardly a household name . . . but an incredibly important person who helped bring about the end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet Union.

Oleg Gordievsky . . . lemme think . . . hardly a household name . . . but an incredibly important person who helped bring about the end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet Union.

Gordievsky was a highly talented, well-trained KGB spy assigned first to Denmark then later to Britain. The British began their recruitment of Gordievsky while he was in Denmark and had completely turned him into a traitor by the time was assigned to the KGB operation in London.

He served there, advancing to director of the KGB operation until he was betrayed by a CIA agent serving the KGB and exfiltrated by the Brits. During his time as a double agent he was more valuable to the British than to the Soviets and that might have gone on much longer than it did had he not been exposed.

All this makes for a pretty good read in Ben Macintyre’s The Spy and the Traitor, but if you are looking for a page-turning spy adventure, look to the pure fiction of Daniel Silva or Ian Fleming. Macintyre gets off to a slow start, spending about half the book developing Gordievsky as a character, much of it spent explaining how passing documents describing ambassadorial and other international and government assignments back and forth was the meat of his work.

The book picks up speed when Gordievsky finally gets to London and gets much more interesting when he makes good work of briefing Margaret Thatcher for her first meeting and ultimately good relationship with Michael Gorbachev. He was credited with giving The Iron Lady the insights and information she needed to establish a basis for an understanding between the USSR and the UK, and ultimately with the United States.

The book really sizzles when Gordievsky, by that time the senior director of the London KGB operation, is recalled to Moscow for “important meetings” during which it becomes clear to him that he has been betrayed.

All through his time as a double agent Gordievsky has been lucky, and his luck holds on this trip to Moscow. Even though it is clear he has been betrayed, the KGB interrogates him and drugs him, but does not assassinate him. That gives him time to signal MI6 that he needs to escape, and the long-planned exfiltration scheme is launched. It works far better than any of its planners thought it would, and Gordievsky lands in London, alas without his wife and children.

He is ultimately honored by the Queen and others, and meets and briefs world leaders. The sad anticlimax of the book and Gordievsky’s story is that his defection and long absence has destroyed his once-idyllic marriage and, although his wife is finally allowed to rejoin him in London, they ultimately split.

I am always flummoxed by how much money is spent on spying by the major and minor players on the world stage. But I was pleased to discover in Gordievsky’s story that all that paper-shuffling and subterfuge could yield positive results.

The Spy and the Traitor is not the best book or even the best spy book I have ever read, but its great historical and educational value trumps its spy story quality all day long.

Recent Comments